- Home

- Iman Humaydan

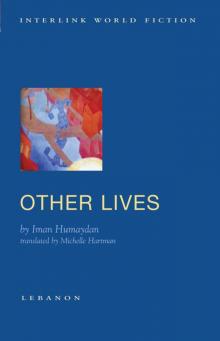

Other Lives

Other Lives Read online

OTHER LIVES

First published in 2014 by

INTERLINK BOOKS

An imprint of Interlink Publishing Group, Inc.

46 Crosby Street, Northampton, Massachusetts 01060

www.interlinkbooks.com

Copyright © Iman Humaydan, 2010 and 2014

English translation © Michelle Hartman, 2014

Cover illustration by Evguenia Evenbach (1889-1981)

Originally published in Arabic as Hayawat Okhra (Beirut: Arrawi, 2010)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Humaydan, Iman.

[Hayawat ukhrá. English]

Other lives / by Iman Humaydan ; translated by Michelle Hartman.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-56656-962-0

I. Hartman, Michelle, translator. II. Title.

PJ7874.U475H3913 2014

892.7'36--dc23

2014002427

Printed and bound in the United States of America

To request a free copy of our 48-page full-color catalog, please call us toll-free at 1-800-238-LINK, visit our website at www.interlinkbooks.com, or write to us at: Interlink Publishing, 46 Crosby Street, Northampton, Massachusetts 01060

For Inaam and May,

eternally here even though they’re gone

When will you be back home?

He asks me on our way to the Mombasa airport. I don’t say that I am coming back. I don’t say that I’m leaving. I only say that I miss Lebanon. I know that longing is not for a specific place. It’s for what’s inside myself that I’m losing everyday, for what I lose while away, for what I’ve created from the images I’ve preserved in my head for so long. It’s as though nothing is left of them now… More than fifteen years have passed since I left. I know that by going back to Beirut, I won’t retrieve what I’ve lost. Instead I’ll simply confirm my loss. I’ll confirm that what I’ve been missing is in my head, only in my head, and I won’t be able to convey it to him.

I leave Chris behind. And I leave his letter to me on my bedside table, without opening it. I know what’s inside: money I don’t want and a question about when I’ll come back to him. Since we’ve been married, he’s left me money in envelopes. Our hands have never touched, not even once, when he’s given me money.

The day before my trip from Kenya to Lebanon, Chris is busy in his laboratory when I call him. His assistant answers. I hang up so that Chris can call me back a few moments later. He’s so completely taken up with what he wants to say that he doesn’t even ask what I want. In an excited, anxious voice—almost crying—he informs me that he’s gotten amazing results from the experiments he began a year ago. Of course he’s happy with the results of his experiments. But his happiness doesn’t make me forget either my decision or my anxious desire to pack and lock my suitcases and put them by the door. I open an empty suitcase and without thinking put some clothes and other things in it. I start by opening the drawers in my wardrobe, take out my underwear, cotton t-shirts and jeans. After I pile them up on the bed, I think it’s too much—I should get used to traveling lighter.

I tell myself that the airplane is taking off tomorrow morning at eight, so I have to be at the airport at six. This means I have to wake up at four in the morning—it’s already past midnight and I haven’t slept yet. I’m going to travel first from Mombasa to Nairobi. I don’t know how long I’ll have to wait in the airport there until the plane carries me to Dubai and then to Lebanon. Chris will accompany me on my journey as far as the Nairobi airport. Then he’ll come back to Mombasa where our house and his work are. I won’t miss anything. This is what I tell myself when I visit the rooms of the house where I’ve lived for eleven years and haven’t left except for a quick trip to Adelaide every year, where my unbalanced father, Salama, and my silent mother, Nadia, live. Or for a short break to South Africa. I don’t leave him except for intermittent weekend trips. I used to travel from Mombasa to Nairobi to pick up things that Olga sent me from Beirut. The English-language lessons dedicated to eradicating illiteracy that I used to give at UNICEF schools in Mombasa were not enough to fill periods of time as vast as the Kenyan plains, nor were the private Arabic lessons I used to teach. I’ve never gotten to know Kenya, despite going as a tourist on organized trips through the Kenyan mountains, the surrounding savannahs and to its parks and wildlife reserves.

Beirut… How faraway it is now. How many lives have I lived since I left it? I think while closing my second suitcase, pulling it toward the door of the house to leave it there. Did I live many lives or only one life that was enough for many women?

Questions I don’t know how to answer. I’m aware that it didn’t take me long to realize that ever since I left Beirut my life changed. As soon as I arrived in Australia with my incomplete family, everything changed—even the names of holidays and when they fall. The Christmas holiday changed into the summer holiday in Adelaide, the Australian city where I lived for four years before I got married and moved to Kenya. The date of winter’s arrival changed. Winter started coming in July.

We wouldn’t have chosen Adelaide, except that my mother’s brother Yusuf lived there. He left Lebanon before the civil war started. He was an active member of the Syrian Nationalist Party and participated in the coup of 1961, fleeing before the Lebanese army could put him in prison. An Australian man whom he met when he was training at the Tiro, the shooting range near the airport, helped him flee. He arranged travel for him first to Cyprus and from there on to Australia. I was five years old at the time. But I feel as though I can still remember my mother Nadia’s fear and worry about her only brother. Perhaps this was the first shock she ever had, long before my brother Baha’’s death, when she received the false report of her brother Yusuf’s arrest and liquidation. That was before she learned the truth about his rescue and escape from the country.

Nadia remembers the past in relation to the incidents that marked our lifetimes. She tells me that I was born on the day of the tripartite military aggression against Abdel Nasser’s Egypt in 1956 and that she was terrified of losing me while I was still a fetus in her belly on the day of the earthquake in Lebanon which cracked open many houses in the village, including her parents’ house in Hasbaya. She says that my brother Baha’ was born after the events of 1958 in Lebanon, when my father was in prison. She also says that my uncle Yusuf, her brother, left the country to travel abroad a few days after the coup of 1961. Nadia’s no different than my grandmother Nahil, my father’s mother, who sees dates of public importance in the family tree before she sees the names of individuals, to say nothing of the fact that her memory would recall any event in history before it would come up with my date of birth… or even that of Salama, i.e., my father. It’s as though the individual in my family has no story unless the beginning of her or his life can be associated with an important date in history. I’ve often believed that our destinies are linked to these dates that describe our lives, the link mysterious, hard to untangle or reveal.

I don’t know if what I remember of my uncle Yusuf is what I saw and experienced myself or if the stories about him that his sister Nadia, my mother, told made me invent a memory that grew up with me and never left. I believe that I remember the day my uncle was arrested but my grandmother Nahil tells me that I was very little and it’s impossible that I could remember. She tells me that I hadn’t even completed my fifth year of life yet. Despite this, whenever I think about my uncle, I can imagine how angry he must’ve been the night before the coup—how he would’ve cursed th

e government and the state, denouncing so many of its members as traitors.

My uncle Yusuf arrived in Australia and lived in Paradise, one of the small suburbs of Adelaide. I found the name interesting after I learned that the largest cemetery and the first crematorium in the area were located near it. This is also where the Druze who immigrated to Australia built their first cemetery. Perhaps they chose this suburb for its name, which to them means that paradise is always found on earth. Or that it’s a dream deferred, equidistant between earth and heaven.

We had to live in my uncle’s house when we arrived at the beginning of 1980. I hadn’t seen my uncle since I was a small child. He seemed like any Anglo-Saxon who’d been born and raised in Australia, especially with the broad Australian accent that he’d adopted soon after marrying an Australian woman who worked in an office for immigrants and refugees. He’d bought a house in Adelaide and didn’t move from one place to another like most of the Lebanese who arrived on the continent before and during the war. When we emerged into the arrivals hall at the Adelaide airport, my uncle ran toward us, hugging my mother for a long time and crying while he asked her how she was. She said a few incomprehensible words, also choking on her tears. He started reminding her of things that she seemed to have forgotten or things whose details may have been buried under the weight of other memories that forced her to be silent. My mother loosened the knot around her silence while hugging my uncle, murmuring a few words, her eyes filling with tears. She began talking and spoke for a few minutes and then returned to the silence that she’d chosen from the moment of my brother’s death. From then on, from the time of our arrival in Australia, it seemed that her silence began to wear her out—as though what she’d chosen for herself began to exhaust her.

Everything that she’d said about Yusuf is still true. Even though he knew the story of how she fell silent after my brother Baha’’s murder, he was not surprised at her words. But her words surprised me, like summer rain. They revived me and helped me recover from the wearying journey that lasted more than two days. I didn’t care what she’d said about my uncle Yusuf, my only concern was that she had spoken after her long silence. In the car on the way to the house, my uncle hugged her and she cried while my father looked out of the car window at people, buildings and streets. His face was red. Sweat ran down both sides of his head and neck as though he was in a sauna. He was still wearing the woolen sweater that he’d worn to travel in from Lebanon. He insisted that it was winter and wouldn’t take it off even though it was so hot in Adelaide. At that moment he seemed weak and yielding, with no power or might. He stuck his head out of the car window, turning it every which way to look at buildings and people walking by as though watching a film that was whizzing past him. He kept repeating, like a broken record, “Ism Allah, Ism Allah, keep the Evil Eye far away.”

My uncle hadn’t changed, that’s what my mother said. But he had really started to belong to his new country over there—from a Syrian Nationalist to an Australian no different from the Anglo-Saxons. This didn’t prevent him from also being an active and influential member of the Druze association that’s had many different names throughout the different stages of the life of the Druze in Australia. It was first established as the Syrian Druze Association, then after Lebanese independence it became the Lebanese-Australian Association for the Druze. After the emigration of a large number of the Druze to Australia in the 1960s, before the civil war in Lebanon, the name changed three more times. It finally became and remained the Australian Druze Association and Yusuf is now in charge of it.

We stayed in my uncle’s house for a few months before we found a house to move into. We rented a house nearby, in an area with few buildings other than a number of nearly identical houses all lined up next to each other on one side of the street. We left my uncle’s house carrying many things that we’d accumulated. But we’d lost some of my mother’s complicity with my uncle, a complicity that had always felt alive and burning to us, all those years that we were far away from him.

We were not the only Lebanese in the neighborhood; there were many Lebanese families, especially Christians and Druze. Five Lebanese families lived on our same street. Others lived on the streets that branched off ours and it didn’t take us long to meet them. Their gardens revealed that the same people had lived here for a long time. These Lebanese families cared for their gardens and grew trees that reminded them of their villages and perhaps even their homes in the Lebanese mountains.

Adelaide is a city of churches. In the neighborhood where we lived there were at least four small churches that the Christian Lebanese attended every Sunday. These people had had to immigrate again after they were first displaced from their villages in the Lebanese mountains. In the nearby neighborhoods, some of the Protestant churches where only a few people prayed had transformed into banks and coffee shops and real-estate offices and houses for people who were hippies in the sixties.

Perhaps the thing that made my father the happiest about our new house was that it was located near a Lebanese bakery that had opened just one year before we arrived in Adelaide. He would go by himself to the Awaziz Bakery on Victoria Street, which branched off our street, to buy Lebanese bread and manaqeesh covered in olive oil and zaatar. The bakery sold not just bread and manaqeesh but also various pickles, zaatar and sumac, which my mother Nadia bought to put in fattoush. After a while, we started to see other things on the bakery’s shelves, like cinnamon, coffee beans and apple-scented tobacco. Sometimes, in addition to these things, the owner of the bakery stocked small Lebanese flags, made in China, to respond to his customers’ longing for Lebanon.

Why’d you come back to Lebanon? Why’d you return? What can you possibly expect from this country?

Olga repeats these same questions from the moment of my return to Beirut as though she doesn’t know the answer.

Is it true that her incurable illness is what made me come back to Beirut? Or was it the news from the Ministry of the Displaced about reclaiming our house? Or did I come to settle old scores with a war that broke up my family, destroyed our dreams and every kind of permanence? Did I return to search for my friend Georges, who never made it to Australia? I waited for him to join me and he disappeared. They said that he left Lebanon from the port at Jounieh, but he never arrived. Perhaps he was kidnapped. Perhaps he never left and remained in Lebanon—imprisoned, lost or murdered, his corpse buried somewhere that no one in his family can find. He never reached his destination, just like so many people who left their own places for others and never arrived. On the ship that I boarded that day for Larnaca, they said that his name was recorded in the log but that no one had seen him. They said that he bade his family farewell at home and left for the port long before the ship put to sea.

What’d you come back for? Olga repeats, and then when I don’t answer, she draws me to her and hugs me, scattering kisses all over my hair, face, mouth and neck. Angry? she asks me, then repeats her question: What’d you come back for?

Olga’s question takes me back to an earlier fear, one that began long before my trip from Beirut, after my brother Baha’’s death, which was followed soon after by Georges’ disappearance. In my first letter to Olga from Adelaide I wrote, “To kill fear, it isn’t enough to move to another country and live in a new house. It’s already taken root inside of us and so in order to kill it we first have to kill something inside ourselves. Perhaps we have to cut off one of our limbs. I’ve often thought of this as a little suicide. It’s as if we are looking fearlessly right into the eyes of a wild beast, looking at it and trying to kill it. We don’t know at that moment that we are killing most of what’s inside ourselves. But what remains after that? What remains after we’ve killed the fear? Does memory remain, for example? Or does it become like a blank page? And what should we fill it with?”

Olga never wrote to me much, she preferred the telephone. She would call every Thursday. She chose the day and it became our tradition. She used to call me every Thursday and

I would write to her every weekend. There was a continual conversation going on between us, each one of us participating in her own way—I through letters and she through words. Our phone conversation would stretch on too long every time; I would laugh when she’d repeat news she’d already told me, protesting that I hadn’t paid enough attention the week before. She’d finish by saying, “Don’t forget to answer my questions in your letter.” Sometimes a week or more would pass without a phone call from her and when she would speak to me she’d tell me that the phone lines were cut, that Lebanon had become a country where people are maimed, victimized, murdered, slaughtered. She’d tell me that things there were shitty and that for her things were shitty beyond shitty.

“Last time we spoke, you didn’t tell me you were coming so soon…!” Olga comments. She’s harassed me with this same comment since I arrived in Beirut. It’s as though she doubts everything I say and doesn’t believe I’ve returned simply to reclaim the house in Zuqaq al-Blat. I don’t tell Olga that I’ve read her doctor’s report and his description of a treatment that she rejected. I’ve also seen the test analyses and results.

I’ve collected no fewer than thirteen suitcases during my scattered migrations between Lebanon, Australia and Kenya. I put what I need in these suitcases. I still don’t understand why a person would need to empty her suitcases. My suitcase has become my home. I’ve become a suitcase expert—special suitcases for backache, others that hold a lot though they weigh very little. I’ve had to find extra space in my house to put the suitcases, safe places I can get to easily when I need to.

“What a surrealistic life!” My English husband Chris mounts a reserved protest as he counts the suitcases piled one on top of the other.

“How many lives do you need to fill all those?” he asks, adding yet another comment: that I should be reincarnated and live other lives in order to fill all these suitcases. According to him, I do nothing in Mombasa except “try to find a permanent location to store my travel apparatus.” This is how he describes my suitcases, trying to make a joke. When we first knew each other, his sarcastic comments would make me stop and think. I used to believe that there was poetry in his remarks and that he needed great powers of imagination to create these sentences. But with time, I’m no longer interested in these kinds of comments. I no longer laugh at his jokes; instead they make me angry. I now believe that he’s so sarcastic because he can’t understand that I can only calm my fears and ease my time in Mombasa by creating stable, settled places within this kind of temporary residence and deferred departure. I’ve started putting in ear plugs, those little wax balls wrapped in cotton, when he talks nonstop about his research and other ideas. I nod my head, agreeing with what he’s saying as if I’m listening. I see him talking on and on, gesturing with his fingers, hands and arms. He looks like one of those sign-language interpreters on the six o’clock TV news broadcast. When he makes a circular motion with his fingers that means that everything’s going as he wants it to, I don’t really understand him. I laugh and doze off. No doubt I doze off while laughing.

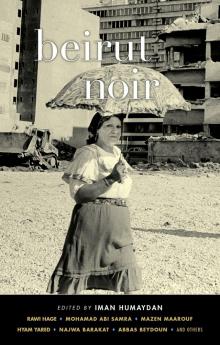

Beirut Noir

Beirut Noir Other Lives

Other Lives