- Home

- Iman Humaydan

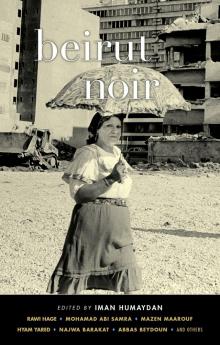

Beirut Noir

Beirut Noir Read online

Table of Contents

___________________

Introduction by Iman Humaydan

PART I: WHEN TIME DOES NOT EXIST

The Bastard

TAREK ABI SAMRA

Chiyah

Maya Rose

ZENA EL KHALIL

Ain el Mreisseh

Pizza Delivery

BANA BEYDOUN

Manara

Under the Tree of Melancholy

NAJWA BARAKAT

Gemmayzeh

Eternity and the Hourglass

HYAM YARED

Trabaud Street

PART II: PANORAMA OF THE SOUL

Beirut Apples

Leila Eid

Bourj Hammoud

Bird Nation

RAWI HAGE

Corniche/Ashrafieh

Dirty Teeth

THE AMAZIN’ SARDINE

Monot Street

The Boxes

MAZEN MAAROUF

Caracas

Rupture

BACHIR HILAL

Tallet al-Khayyat

PART III: WAITING FOR YESTERDAY

The Thread of Life

HALA KAWTHARANI

Bliss Street

Without a Trace

MOHAMAD ABI SAMRA

Raouché

The Death of Adil Uliyyan

ABBAS BEYDOUN

Ras Beirut

Scent of a Woman, Scent of a City

ALAWIYA SOBH

Khandaq al-Ghamiq

Sails on the Sidewalk

MARIE TAWK

Sin el Fil

About the Contributors

Translator's Acknowledgments

Bonus Materials

Excerpt from USA NOIR edited by Johnny Temple

Also in Akashic Noir Series

Akashic Noir Series Awards & Recognition

About Akashic Books

Copyrights & Credits

Dedicated to the memory of Bachir Hilal (1947–2015)

Introduction

Violence of Loneliness, Violence of Mayhem

Beirut is a city of contradiction and paradox. It is an urban and rural city, one of violence and forgiveness, memory and forgetfulness. Beirut is a city of war and peace. This story collection is a part of a vibrant, living recovery of Beirut. Beirut Noir recovers the city once again through writing, through the literary visions of its authors.

Assembling this collection was an ambitious experiment for me; editing it was fascinating and full of challenges. It is by no means easy to bring together a book of fifteen short stories by writers with such different perspectives on Beirut. Fourteen Lebanese writers, and one Palestinian writer born and raised in Beirut, contributed to the book you are holding today. Taken together, their stories reflect the city’s underworld and seedy realities. Each story is only one tiny piece of a larger mosaic; they all coalesce here to offer us a more complete picture of the city.

There are so many clichés we must confront when examining Beirut. It is difficult to write about it without describing it as a city that never sleeps, as the center of life, and also as a city that is the companion of death. These two descriptions are inextricably linked, though they may seem contradictory. Those of us who live here and know the city well recognize these powerful characterizations that we hold in our collective imagination. Elsewhere, I once described Beirut as “the city that dances on its wounds.”

We know that Lebanon is a country with a long and rich history of diverse cultures and religious traditions, as well as a wealth of languages. Every school in Lebanon teaches three languages—Arabic, English, and French; I kept this trilingual background in mind when choosing the stories for this collection. Michelle Hartman, who has previously translated two of my novels, meticulously translated these stories from both Arabic and French into English; there are also three stories originally written in English.

* * *

From within this collection of stories, a general attitude toward Beirut emerges: the city is viewed from a position of critique, doubt, disappointment, and despair. The stories reveal a vast maze of a city that can’t be found in tourist brochures or nostalgic depictions that are completely out of touch with reality. Perhaps this goes without saying in a collection of stories titled Beirut Noir. But the “noir” label here should be viewed from multiple angles, as it takes on many different forms in the stories. No doubt this is because it overlaps with the distinct moments that Beirut has lived through.

All of the stories are somehow framed by the Lebanese civil war, which lasted from approximately 1974 until 1990. The war here serves as a boundary between the memories of the authors and the memories of their characters. Indeed, whether the stories include time frames during, before, or after the war, all of them invoke this period somehow—even if only to recall other times of which nothing remains.

Some of the stories explore the memory of people wounded by Beirut during the war, who have not yet healed. These works include Mohamad Abi Samra’s “Without a Trace,” Leila Eid’s “Beirut Apples,” Marie Tawk’s “Sails on the Sidewalk,” Abbas Beydoun’s “The Death of Adil Uliyyan,” Bachir Hilal’s “Rupture,” and Hala Kawtharani’s “The Thread of Life.” Other stories are told by new and fresh voices born amidst the violence of this war. These brim with playfulness within their dark visions, such as Hyam Yared’s “Eternity and the Hourglass,” Najwa Barakat’s “Under the Tree of Melancholy,” and “Dirty Teeth” by a young author writing under the name of The Amazin’ Sardine. Some suggest the complexities of class issues in a society marked by sectarianism, like Tarek Abi Samra’s “The Bastard” or Mazen Maarouf’s “The Boxes.”

While the tales might be playful, the characters’ lives can be unstable, and they often have no confidence whatsoever in the future. Despite this, we laugh darkly while reading Bana Beydoun’s “Pizza Delivery”—its melancholia takes us right to the limit of what we can find humorous. This is also true of Rawi Hage’s “Bird Nation,” as well as the stories by Hyam Yared and Bachir Hilal. Beirut is like that. So much gloom and wasted lives; we weep even as we laugh. In Beirut, chaos is a way of life.

This is not all there is to Beirut though. The city is still crowded and on the move; indeed, it can be boisterous at night. But these crowds and mayhem are not the same as those during the day. Beirut nights are different. It’s as if in the absence of day, the city is freed from its severity. Nighttime somehow softens its harshness and anxiety; the city can be seen in its lights reflecting off the sea, its expansive sweep under the nearby mountains, and its truly beautiful vistas. The contributions from Bana Beydoun and Mazen Zahreddine offer portraits of the city at night, through the lives of young people born after the war. This is a Beirut where the violence of loneliness and the violence of mayhem come together.

Chaos reigns here—it is the source not only of violence but also the diversity and dynamism of every aspect of the city. Most stories in the collection confirm this—but especially those by Rawi Hage, Zena el Khalil, and Alawiya Sobh.

And yet time is precious in Beirut. Hyam Yared’s story, centered around an hourglass, is a reflection of the fear people have of time flowing through our fingers and being lost, just as Lebanese people lost fifteen years of their lives during the civil war.

Through the eyes of the dead child who is the eponymous narrator of el Khalil’s “Maya Rose,” we see a panoramic scene of Beirut’s coastline from above the Corniche by the lighthouse and beyond. This story, like the entirety of Beirut Noir, allows us to glimpse beautiful things in Beirut, even as it wakes and sleeps in violence and disorder.

Beirut lives through time, always oscillating between war and peace; these moments make Beirut Noir’s scenery as naked as the edge of a knife.

Iman Humaydan

Beirut, Lebanon

September 2015

PART I

When Time Does Not Exist

The Bastard

by TAREK ABI SAMRA

Chiyah

1.

They were born on the same night, of the same father but different mothers.

That day, unusual disorder in the hospital meant that they were confused with one another. When their progenitor grumpily leaned over to examine this pair of twisted-up, crying red faces, he hesitated for a moment—they definitely resembled him, but not their mothers. Then, deciding at random, he designated which was to be the bastard with one disdainful gesture of his hand.

One was the offspring of his wife, a sickly woman who died in childbirth. The other was the maid’s, a beautiful young peasant woman who was vigorously healthy. Thanks to his many ties to the ministry, he was able to get both children recognized as legitimate. Nonetheless, at home each one forever occupied the position assigned to him by that paternal gesture.

2.

As children, they liked each other well enough and often played together, but at the same time they were jealous of one another for completely opposite reasons.

From the most tender of ages, the so-called bastard was aware of the total dishonor of his status; his mother’s smiling eyes hardly compensated for the contemptuous pity, mixed with slight disgust, that he inspired with every look from a friend or stranger. He experienced this contemptuous pity viscerally: he experienced it like a cramping in his abdomen; he experienced it like an urgent need to vomit.

As for the supposedly legitimate son, you could have attributed his small stature to the fact that he was completely flattened by his father’s tyranny. Though his father was uneducated, the boy was destined to become a doctor—a great doctor. And according to a magnanimous decree, he was always meant not just to be near the top of his class, but among the top five. Fear and determination offset his mediocre intelligence and he almost always succeeded at keeping himself in the third or fourth position, even at the cost of the most beastly indignities.

3.

Though he was rich, the father resided in the bustling neighborhood of Chiyah, on Assaad al-Assaad Street, where he owned a building and lived in an apartment on its top floor. Adjacent to the building, a low, little house of two excessively narrow rooms—built in a rush a few months before he was born—served as the lodgings for the bastard and his mother. The bastard never entered his half-brother’s bedroom. In fact, the whole apartment was off-limits to him, their father being unable to stand anything that might unite the two children. It was the same for the legitimate son: crossing the low, little house’s threshold was absolutely forbidden. The possibility of any exchange between this child and his other potential mother—the maid who had been his mistress—terrified the father. Nonetheless, even the laws of the universe were unable to stop them from killing time together. And they often played together in the mud behind the low, little house.

There was a small sandy enclosure just behind the bastard’s house where they met daily—at dawn during vacations, in the afternoon on school days. The father often sent the building’s doorman to bring the legitimate son home, dragging him by the ear.

Usually, they filled buckets with water that they mixed with earth to make mud projectiles to throw at each other. You would have said that each one was relieved of his shame by splattering his half-brother’s face with mud. In fact, each aspired to the other’s misfortune: the scorned one coveted respect; the slave, his freedom. One evening, when they were twelve years old and amusing themselves by smearing mud beside their house, the so-called bastard said proudly to the supposedly legitimate son, “You don’t have to worry about anything, your life is so easy! Your future is secure, you have money and a father.”

Wounded, his brother didn’t know how to respond at first and started to cry. Finally, he stammered through his tears, “But at least you’re allowed to play when you want. And you also have a mother.”

4.

The bastard enjoyed an unprecedented popularity at his school . . . their school. His ugliness—unlike his brother’s—didn’t at all prevent him from being popular among the female students: whenever he’d appear, it was as though their clitorises transformed into claws and tore viciously into their flesh. By the time he graduated with his baccalaureate he’d already deflowered a dozen—the other was still even less than a virgin.

The one, according to plan, enrolled in medical school. The other, leaving the low, little house a few months before his mother’s death, was hired as a waiter and began studying law. They didn’t see each other for three years.

5.

The Communist epidemic was palpable in the air; from one day to the next, it intoxicated a significant number of student brains.

Every evening, the local bar transformed into a forum for heated political debates. One particular Friday, the controversies grew so ferocious that people came to blows with fists, glasses, bottles, and chairs. After the owner was finally able to evict this thunderous crowd, drunk on alcohol and ideas, two young men recognized one another outside in the dark. They each walked alone, on opposite sides of the wide street, their footsteps drawing parallel paths. It was dark, but a few weak moonbeams surreptitiously pierced through the heavy cloud, and then two giant, thin, infinitely stretched-out shadows were drawn at a diagonal behind each of their backs. They pretended not to notice each other but from time to time shot over quick, furtive glances.

This farce had already lasted a good while when the bastard had an idea that made him stop cold. So he crossed the street. Seeing him approach, the other one, paralyzed, nervously chewed on his lower lip and stared: unspeakable hopes were aroused in his heart that left him nonetheless vaguely sensing a tragic outcome. When they were face to face, the bastard—putting on a somewhat ironic grimace—exclaimed with affected surprise: “But someone might say that this is my brother!”

“Or rather your half-brother,” the other one immediately corrected him. Still, he found it impossible to pull himself away physically, but believed instead that the extreme precision of his comment could at least establish a certain distance in their kinship.

“Whatever,” said the bastard, calm and condescending, instinctively seizing upon the futility of his brother’s gesture. Using his old favorite childhood way of teasing, which despite its terseness reminded the other one of the full extent of his subjugation, he said, “So then, doctor, sir, how are you today?” After a moment of mutual discomfort, he sharply added, “Let’s walk a little,” to put an end to the brief silence.

The sun had already risen and the two brothers were still walking. They had spoken feverishly all night long. After they separated, each one, desperately trying to fall asleep in his own bed, tried in vain to repress some bits of this long nocturnal conversation.

In his head, the legitimate son mostly replayed their discussion about communism, which fascinated him to no end. The subject had somewhat concerned him during this past year, but until now he had been content to simply pay it modest attention without getting carried away by the general frenzy which had gradually gained ground inside the universities. Yet just a few hours had been enough for his brother’s eloquence to, quite simply, ignite him. He was taken by a boundless admiration for the People, and henceforth considered himself a devoted supporter of the cause. For the first time in his life, this freedom that he so coveted but rarely knew became incarnate; it took form, nearly flesh and bone. He was possessed by unprecedented pleasure, but soon he found himself tumbling into a terror that grabbed him by the neck and strangled him.

Ideas from the same conversation, but utterly different in content, scuttled through the bastard’s mind while he lay in bed, staring at the ceiling. The enthusiasm he knew so well how to inject into his brother had clearly shown him the true extent of his capabilities. In truth, possessing a superior mind as well as a highly independent and excessively reckless character, he

never once missed out on exercising a certain influence over this submissive being. Meanwhile, his brother could offer no resistance to the absolute domination that the bastard knew he was now capable of: he would steal this son away from his father. Moving back into his old house was the first thing that he intended to do.

6.

The father had sold his building on Assaad al-Assaad Street two years before, and the new owner, with the intention of building a much bigger structure there, planned to demolish it at the same time as the low, little house that had once served as lodgings for the so-called bastard. But the outbreak of the civil war had caused him to postpone his project.

It was the very inevitability of its destruction that compelled the bastard to rent his old house three years after having left it, when his mother died and he started at university. He wanted to recall bits of his past, but didn’t really know which ones.

Just like an old man whose still-recognizable features have been ravaged by the passing of time, when his feet first trod upon Assaad al-Assaad Street after these years of absence, it still seemed familiar to him. Yet at the same time it was so disfigured by the war that he felt a vague but intense pity toward everything there—the buildings riddled by machine guns, some of which had lost sections of their walls and even entire facades following bombardments, the asphalt cracked and full of holes, the smashed sidewalks that had almost disappeared, the burned-out cars, the bored, smoking militiamen weighed down by Kalashnikovs.

He found all of the old furniture of the low, little house well preserved but faded and smelling damp. He moved in right away, cleaned a little bit, but changed nothing, not even the furniture.

7.

Another meeting took place, others followed it, and then came a time when the two half-brothers could hardly do anything without one another. Nonetheless, a vague sense of apprehension stopped the legitimate son from visiting the bastard’s house; he imagined a sort of curse hovering above Assaad al-Assaad Street.

Beirut Noir

Beirut Noir Other Lives

Other Lives