- Home

- Iman Humaydan

Beirut Noir Page 14

Beirut Noir Read online

Page 14

If Nazmi had been here he would have learned it easily. If he’d been able to hear me, I would have said to him, “It isn’t difficult at all. We do it just like this. It’s like when we close our eyes, like usual. But for this we close only one eye, and the other one we don’t use . . . We keep it open.” I made a distance between the first finger on my hand—the first thick, short finger—and the second one that we use to point out new places to people. Then I unzipped the bag. I opened my two fingers to the size of a star and the space between them seemed bigger than all the small boxes. I closed the bag right away. I sat on the flimsy edge of the roof. But it wasn’t going to collapse, otherwise I wouldn’t sit there. I started getting sleepy. I dozed off a bit. Then I woke up. The floor where Nazmi lived, in the fifth building on the way down the incline, was not lit up. I kept looking at the half of the apartment where he lived with his family. I could perhaps notice some movement in the kitchen, behind the giant glass doors and the clothesline. I threw a look from where I was to the entrance of the building, but I got dizzy and was afraid to lose my balance and fall. I took out the halawa sandwich that Nazmi and I were supposed to share and devoured it. It was stale. I believed it would help me not to faint. I didn’t leave him even a bite.

The stars were still crashing into each other. And the sound was loud. So much so that people left their houses. They were carrying their belongings and bringing their children out. The police were waiting under the building to be sure everyone left. After a little while my father came, angrily. He slapped me and took me by the hand and emptied the boxes onto the roof. No, it’s not good for my reputation that I accuse my father of that. I’m the one who emptied the boxes. I left the building with him, we left the building together. Me and my father and my mother. My mother was crying too and threatening that she’d make me pay for this later in our new house. I saw a lot of people leaving, emptying their apartments, evicting themselves from the building. They shook hands quickly, then jumped in their cars, revved their motors, and took off without looking back.

There was a car waiting for us as well. I sat next to the window. From my spot, I couldn’t see the half of the apartment Nazmi and his family lived in. I saw the people from the other family who lived in the other half of the apartment. All of them were on the balcony. I wanted to speak to them, I waved at them, but no one saw me. My hand was small and it was dark. Everyone was screaming—the policemen, children, women, the men in the pickup trucks. Everyone. I thought about doing something clever. So clever that no one around us—me, my mother, and my father—could guess. I lifted my head and looked at the stars. They had stopped quarreling. They went back to their natural size. I measured them again with the same new method. And I grew sad. Sad for the small wooden boxes left there. My feeling of sadness soon faded, however. Quickly. With the speed of a star which crashed into its sister. Just as quickly my sadness faded at the thought that Nazmi would come up to the roof after leaving all the people and the police, and he would complete what we had started together. I only hoped that he would close his eyes tight.

4.

After our departure from the building, a rumor started that the police hadn’t come because of the noise of the stars crashing into each other. But rather because of the colonel who lived in the building across the street. People used to hate him and the police who gathered by his house. He was always grouchy. But I doubted this rumor. I’d never seen the colonel harm anyone and I used to sometimes defend him to Nazmi on the roof. I would say, “He probably saw something bad today and he’s grouchy because he’s sad.”

I defended him even though I didn’t need to, and Nazmi would interrupt me, saying, “Why don’t we start throwing boxes?”

Perhaps I said that because I thought I loved his daughter Dalia and thought she’d love me when she grew up. In the morning I would stand behind the window, holding a big mug of hot milk. But I wouldn’t start drinking from it until I saw her come and stand in the window of her own house, across from me. She wasn’t standing behind the window for my sake. But to watch the street, the cars, and the military jeeps waiting for her father down below. She used to watch every idea, person, and cat on the incline except me. Like me, she carried a mug that I always convinced myself also had milk in it. Perhaps this mug had special maramiya herbal tea to treat diarrhea or mint tea to stop her vomiting or some other drink to improve her breath. But I always believed that there was milk in her mug. On the days when Dalia didn’t stand behind the window, I poured my milk out into the potted plants. Their lactose increased daily until they’d become so much lighter you could no longer say that they were green.

I imagined that Dalia lived in a palace. A palace squeezed onto the first floor of the building across the street. Our house was also on the first floor but she never once looked in my direction. In the beginning I thought it was because of the wide street separating our two buildings. I said surely our house is very, very far from the building across the street. I concluded from this that Dalia was younger than me, much younger. That the people, like me, who can cross the street from our building to the one facing it easily take giant footsteps. If you didn’t take giant footsteps you couldn’t see faraway places, like Dalia’s house. Dalia couldn’t see me because of her tiny footsteps and her youth. In order for me to help her realize that she lived near us, in our space with us, the children older than her, I wanted to rename Caracas Hill the Colonel’s Hill.

I asked Nazmi to promote the new name. But he was afraid and warned me, “Perhaps the colonel will get angry, shoot the wooden boxes, and knock them down from above.” Later I learned that Dalia had been sent abroad to a a faraway country with a forest to receive some kind of treatment.

5.

The letter reached me. From Nazmi. It was written on the back of an invoice from the shop. On the back there were a lot of numbers and on the front, words. Two groups. Numbers also have a long life, which we don’t understand at all. Numbers have been breeding and giving birth to other numbers for hundreds of years, though all we do is count them; we believe that when we cross them out, they’re gone. But actually they nest in invoices and walls, heads and files. Most of them are found inside our stores of phenomenal forgetfulness. These stores of forgetfulness fill up every day with new numbers. And the numbers there get to know their relatives that have also been divided for generations. But before they get to these stores they walk close by us most of the time, though we only feel them when they are written down on paper. They decrease when we die and increase if the opposite happens. We also know nothing about their feelings. Or their voices. But then they appear as long as electricity cables, and connect cities and people together. Sometimes they connect two boys. Like Nazmi and me, for example. Even if one of them is lying on his back in a hospital and the other is lying on his back at home. And for this to happen, these two boys lying on their backs must think about the same secret. Even this secret is merely a handful of stars in the sky, where they never saw a wooden box arrive.

* * *

“I won’t be able to meet you on the roof of the building after today. I hope this doesn’t upset you. I have a room now. In a faraway hospital with a big warm bed. It’s well lit. It has lamps in it that you can’t find in the shops. If I improve my behavior they may put in a television for me. Perhaps a small television, perhaps not. Sometimes I entertain myself by looking at the fluid dripping through the IV tube but that gets boring fast. The sound of these drops is muffled. I have gotten to know all the little sounds without being forced to hear them. But all the muffled sounds are distant at the end of the day. Even the drops of medicine, which scramble around inside the veins in my arm, seem very distant because they are muffled. They are not as close as they seem or very close at all. I feel like they aren’t mine. I dream that I’m pushing a long train with my hands, a train carrying all the stars in the sky in coal carts. It’s true that I’ve never seen a train except on a chewing gum wrapper in the shop, but I’ve dreamed of a train. It was

also yellow and pink. The stars were dusty and my hands were big. Bigger than they should be, and thicker too. Because of this my back is bowed and you see me hunched over toward the ground. When I woke up I was thinking about the locust. I don’t know where the train has arrived. The locust we found on the roof, do you have any news about it? I urged you that day to open one of the boxes and put it inside. You had to do it. We put the locust inside, we resealed the box and threw it with the other boxes. I closed my eyes with all my strength. Sometimes I think that this locust is eating a little piece of the moon, that it tricked us and didn’t reach the stars. I hope I’m mistaken, but after my mother falls asleep in the chair, I go up to the roof of the hospital and look at the moon. Sometimes it seems to me that its color has changed on one of its sides. I fear that the locust is eating it. Are you sure the moon is so big that it can keep rising above people’s houses even after we did this? Can you send it some gauze? In boxes? The gauze could fill in the missing, eaten part and no one will notice. In the hospital no one asks me where I’m going. I leave my room and steal down the stairs. I can’t take the bag of medicine out of my arm but I drag it with me on a metal pole. On the roof I’m completely alone. I close my eyes as tightly as I can like I always used to do when I was with you. And I lift my head up. Toward the sky. It seems to me that when I close my eyes, the color of the sky suddenly changes and becomes the color of the little strap around a gas canister. That thing we put between the screw-top and the tube so that gas wouldn’t leak. I think that perhaps the night is this layer of artificial leather that prevents our dreams from leaking out of us and rising. Up above the sky. To what is above the night. Did you ever wonder what we could find sitting up above the night? But after I close my eyes, I totally know when to open them. Yes. At the very moment you stop throwing boxes on the roof of the building, I open my eyes here on the hospital roof, holding onto the medicine pole with both hands because I’m exhausted. I won’t open my eyes except when you ask me to.”

6.

I wanted to tell Nazmi more of the secrets connected to the boxes. When we threw them in the air, they rose, slithering along invisible tracks. Tracks like the chains of the only swing at the amusement park. Every box takes a different sinuous route from every other box (and to make it easier, I would have to ask Nazmi to imagine the pipes of the sink instead of imagining the amusement park chains on a winding frame). With distance, feverish boxes grow hotter and open the moment they arrive at the star. No box pays attention to its right or left. It doesn’t look at any other box, nor at the passengers who wave at it from the airplane, nor at high-flying birds, nor even at the boats in the sea or the beams from the black-and-white-striped lighthouse on the street parallel to ours. It doesn’t pay attention to anything, but instead passes on its way, concentrating on how to not waste energy for nothing and to not be delayed in arriving at its desired star.

But Nazmi went to hospital the day before we left the building. My parents had decided to leave and hadn’t informed me of this ahead of time. This surprised me, so I was forced to leave with them at the last minute. Were it not for that I would have stayed. I would have hidden in the electricity room that gave off the stench of urine soaked into the land under the building. I would have lived inside it and finished preparing all the boxes there. We left because the war began. But the war at that time was still small. Like children. It wasn’t more than sounds that came and went. Personally, I didn’t see the war at all. I didn’t see anything, therefore I can’t tell you anything about it. They started to talk about it on the radio at the time and stopped talking about anything else. But the sound of the war wasn’t like the sound of the radio. Its sound wasn’t like any spoken word. It wasn’t like Nazmi’s voice or even the sounds of the boxes after they are thrown. The colonel also left for the mountains. Nazmi didn’t come to the roof of the building the night before or the night we left. When I finally read his letter, it was after he’d already died of leukemia, blood cancer, more than three years earlier. I wished that I hadn’t ever gotten close to the gas-canister boy. I felt kind of jealous of him because he died. Nazmi became this precious piece of paper that I folded in the small wooden boxes. Without him, I couldn’t unfold this paper anymore or even see the boxes as I saw them before.

When I entered the shop to get some wooden vegetable crates that first time, Nazmi asked me what I was going to do with them. I said, “Boxes.” Because I didn’t want to tell him what I thought about the desultory things in the world, I added the word stars to the word boxes. So it became, “Boxes for stars.” Then I finished, “Small boxes, I throw them in the sky when it’s dark outside.”

“What do you mean by stars?”

“They are small bodies that shine in the sky at night. Like little crumbs of bread.”

“I never thought about looking at the sky before. I spend my days moving things, canisters of gas, for the people who live on this street. Everything is heavy. I hate all heavy things and avoid looking at them when I can. Therefore I don’t look at the sky. Because the sky is itself a heavy thing. Don’t you think? At school, don’t you study how heavy the sky is?”

Nazmi refused to give me any crates that day. But the next afternoon he knocked on the door of our house and had three crates with him. He said excitedly, “These wooden crates are for you. Can I come with you when you throw the boxes at the sky? How many boxes can you complete by tomorrow?”

“I don’t know, I will try as hard as I can,” I answered him, bewildered.

“I can bring you string, glue, and nails—yes, even gas-canister wrenches. I will tell the owner of the shop that they fell out of my pocket. He will punish me but his punishment won’t last for more than one day. Could a wrench be helpful in preparing boxes?”

Nazmi brought me string, glue, and nails. I don’t know where he got them. As for the wrench, I refused to accept it because it was too heavy for me.

The next day I found Nazmi standing in front of me. He asked, “Can I go with you? I won’t look at the star you are looking at. I will look at another star.”

But I stipulated that he should close his eyes and I would throw the boxes. Like him, I closed my eyes. Because the boxes won’t get anywhere if an eye can see them. The pupil of the eye is small and if we look at the box with it, the box will be inside it. And in that case it won’t be able to get out. Instead, it would plunge into the depths of his eye, inside his head, and from there would sink toward his chest, stomach, and intestines. There are no stars in the intestines. It will generate a pain in the teeth when its muscles start pushing the box slowly, from the belly on up, to leave our mouths when we’re sleeping. Not all muscles do that, only children’s muscles. What I said to Nazmi was true, so I also used to be afraid to look at the boxes while I was throwing them. After doing this, I left the roof immediately.

* * *

Like all people, Nazmi had two rows of teeth. But when he closed his mouth they didn’t line up on top of each other evenly. I used to always see a space between them. For that reason Nazmi was unable to pronounce some letters: tha’, jeem, dhal, zay, seen, and sahd. All of these letters used to come out of his mouth the same, like a combination of the sounds for sheen and sahd. Once on the roof of the building I tried to teach him correct pronunciation. But he started to cry, and I asked him why he was crying, acting like I was angry, trying to stop myself from bursting into tears like him. But he didn’t tell me why he was crying. He didn’t tell me anything. He calmed down and asked me not to try to teach him pronunciation again. He had to hear himself pronounce the names of things wrong, but knowing at the same time that he couldn’t correct them. He wanted these things, which belonged to life, to be disturbed when hearing their names pronounced by people incorrectly.

“No doubt, everything in the world has gotten used to hearing its name like this for a long time now,” he would say.

I used to answer him, “I believe that. In class, the teacher said that sky, sun, clouds, pebble, purple, evil, b

ox, rainbow, star, and others are things that didn’t change their names for hundreds and hundreds of years.”

Then he asked, “But these things, have their forms not dwindled since this time called ‘hundreds and hundreds of years ago’? Is it possible that some form fades away but its name stays the same?”

I didn’t answer these complex questions of his but I felt that they’d sprouted up in his mind because of the shape of his two big hands.

* * *

The roof of the building wasn’t pretty and it wasn’t clean. Rusted, broken antennas, the rubble of rocks, a broken clothesline, and water tanks were strewn around on it. But from atop we used to be able to see Beirut’s lighthouse. It was a column, standing on a hill, shining at night. The lighthouse might have seemed very tall to someone looking at it but it wasn’t. It was short and thick. What was actually raised up was the hill underneath it. We also used to see the water. The entire sea, right to its very end. At the end of the sea there was a horizontal blue line that had a starting point and an ending point. These two points seemed sturdy, as if nothing could move them, and the mainland shrunk with every dot as if a clamp was holding it fixed in place. We used to see a lot of swimming pools. Three or perhaps four. One of them used to stay lit at night because it was for the soldiers and secret police. There were always elderly divers swimming extremely slowly and carrying fishing nets on their shoulders. We used to distinguish them by the gleam of the flashlight that they carried in their hands. Then on the back side we used to be able to look out over the al-Aoud family’s big garden in which many kinds of trees grew, like pomegranates, guava, and bitter oranges, where both distant and nearby birds used to come and sometimes chirp at night. But that didn’t concern us. Similarly, we used to look over two tennis courts at the sports club called “Escape” in English. Then there was, in a distant area far from the sea, a football stadium for some professional team. Nazmi and I concluded that this stadium was miles longer and wider than the corridor of our building. There was a Ferris wheel in Beirut’s amusement park which never stopped turning; in the winter the wind would come to the sea to play with it and make it turn around to the left and right.

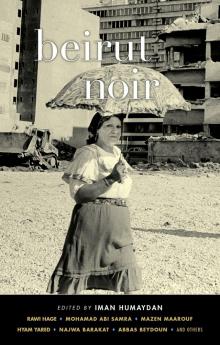

Beirut Noir

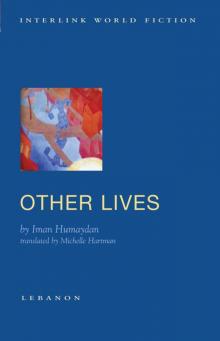

Beirut Noir Other Lives

Other Lives