- Home

- Iman Humaydan

Beirut Noir Page 21

Beirut Noir Read online

Page 21

He finally reached an old story that he was still proud of and wanted his wife to hear. It’s the story of a practical joke he played on me. We were sitting beside a natural spring, one of those places that feels like it’s inside the earth, perpetually dark. We arrived there at the end of a day’s outing during which we’d eaten a picnic lunch outside. He took out two plates, gave me one, and told me to do as he did. I don’t remember the reason he gave but I assented in order to please him—I couldn’t say no to my friend on the trip that day. He scooped up water from a little stream and I followed. He started dipping his fingers into the water on his plate, passing them under the plate, and then rubbing them all over his face. I did the same. He repeated this and I imitated him until we stopped. Then we left. We crossed the village square together and then parted to go home. I didn’t yet know that my face was stained with charcoal; there had been sooty charcoal under my plate that had stuck to my damp fingers. Even now—almost forty years later—Adil’s still proud that he was with me when my face was covered in soot in the middle of the town square and everyone laughed at me. This was the go-to episode that he’d recall whenever we met.

Up until this day, I’d never known him to have the ethical disposition to be ashamed of himself for putting a friend in this kind of situation, one that started out as a joke but turned to malice. His smugness about his own cleverness and the success of his prank has remained the same—from when he was fifteen until now that he’s over fifty. From this incident, something childish developed within him and remained there. No doubt this same childish thing was also present in the cartridge of bullets he emptied into the head of the customs man. And no doubt this childish impulse has accompanied him on all his exploits and malicious deeds. He’s the child who plays practical jokes to get attention—amusing people or terrorizing them, there’s no difference.

From that day on, whenever I’d meet Adil Uliyyan he’d retell this story in front of his wife, as though by doing so he could relive it in the present and make Rosette and his daughter Line, who sometimes sat with us, laugh at me. He kept returning to it until I felt that he was humiliating me once again, and that I was a victim of his prank anew. I told him that he hadn’t grown up yet. That he’s still a little boy playing jokes and that he needs to get a life instead of ruminating over these kinds of stories. He recoiled a little bit when I said this, but it didn’t stop him from retelling the story the very next time we met. What really surprised me was how pleased Rosette was by how I spoke to him. Indeed, the way she looked at me while I was talking encouraged me to carry on . . . The same was true of his daughter Line. The two of them paid me full attention while I talked. They wanted me to keep going and from that time on they started welcoming me warmly, as though I had become part of the family.

* * *

The voice of a woman on the other end of the line told me that Mr. Adil wanted to speak to me. Adil then took the phone, his rattling voice coming over the wire, laughing and congratulating me on my grandmother becoming a saint. He said that no doubt some of her saintliness would stick to her children and grandchildren. The whole family would become holy. Despite his playfulness, I could sense anxiety in his voice. He told me that he wanted to see me. Could I find the time to come by his place that day? What about stopping by in the evening so we could drink tea together? I dressed carefully: a brown leather jacket with light-colored jeans; it’s appropriate to maintain a proper appearance in front of Rosette.

When I got there, the servant came and told me that “Baba” was waiting for me in his room. I went up to the second floor and Adil called me into the family room. He told me that Rosette and Line were out shopping. I felt a bit frustrated; it would have been better if Rosette were sitting with us. I liked it when she was there, or at least I didn’t like to be alone with Adil. He was in his dressing gown and slippers and was stretched out on the long sofa that was the only one of its kind in the room, as if it were designed just for him. Struggling to stand up to greet me, he motioned me to the sofa across from him. I entreated him to remain seated and walked over to shake his hand.

We stayed silent for a while, until Adil pressed a button in the arm of the sofa and a servant came. He asked her to make tea. Then he started talking about my grandmother, picking back up where we’d left off that morning on the phone. He wanted to start the conversation between us like this, forging a path through laughter. When the tea arrived, Adil lifted his glass, and as he brought it close to his mouth, he said that he wanted to confide something very important. I promised him that it would remain between us, but I told him explicitly that I don’t like carrying around people’s secrets because it makes me feel an unbearable responsibility; I don’t want to share anything with anyone that isn’t my business. I really didn’t feel any desire to know his secret and hoped that he would leave me free of this burden. But all my excuses only loosened his tongue. He stretched out even more on his sofa and told me that there was something he didn’t want to take to the grave with him. He didn’t know what motivated him to confide it in me. But the day before he’d cooked up an idea in his head and decided to just do it; there was something he wanted to get off his chest, something boiling deep inside his heart he wanted to let out.

He said, “You know that when I was first in Beirut, I belonged to the Pioneers of the Revolution. And as you know, this unit had a strong moral code. Before long, people in the organization started stealing cars. I acted against the rest of the group and refused to join in, but it was war. The rules just fell away of their own accord, without anyone noticing. The group’s harsh discipline helped in stealing cars. Murder was easy. Before we all became isolated, we organized together and we killed because of sectarian identity. Then sniping started on the other side and it soon moved to our side. Soldiers became proxies to do anything and everything. It was war and we had to win at any cost.

“One day, Commander Suleiman called us in. There were ten of us. He said they were sending us to train as snipers. We learned to target anything, any person who crossed through the little square box that we saw through the sights of our guns. I learned fast. No target escaped me. We went up to the roofs or top floors of buildings in Chiyah and we started sniping across in Ain al-Rummaneh. For me, it was fate that moved people into the little square box. I had no hand in it; I was simply working in the service of fate. You will ask me if I looked into the eyes of any of my victims. I will tell you that it’s not possible to see eyes in the sights. It’s a game of fate. So when someone fell on the first shot it meant that his time had run out and we couldn’t do anything for him because this was his fate. I don’t want to hide from you—I don’t feel any guilt. Those people who kill for sectarian identity listen to their victims’ pleas. We listened to nothing but our bullets and looked at nothing but what they hit. It’s sport, totally clean killing. I didn’t read the newspapers and didn’t want to know my victims’ names. I didn’t want to see their pictures. I’m not the one responsible. They’re the ones who walked into my sights, into the little square box. If someone took one step backward and was saved, that wasn’t my doing, it was because it was his fate. They used to talk about their victims; I never did. As soon as the event happened I washed my hands of it. I acted as if I didn’t do it. In the end I succeeded in convincing myself that it wasn’t me who did it. It’s an instant, and I’m not even totally convinced it happened.

“Once a man and his son walked by. I targeted them in my sights. Then I noticed that his son sort of resembled my daughter. I noticed that the man looked like me. Out there were two people who looked like my kid and me; I suddenly didn’t want to kill them. But they were inside the little square box. I wanted at least not to target the child. But fate intervened and the child fell. At that moment, I felt that I became my daughter. That I had targeted myself. I quickly ran downstairs from the top of the building to the street; people were still gathered around. I took another road. I fled. That time, I felt I was a coward. I fled from fate, from my fate.

It was condemning me. When that coward emptied his gun into me, I immediately remembered the child falling down. It was as if my own shot had come back to hit me, as if it were ricocheting back at me from that place.”

* * *

A stormy morning froze Beirut. Adil Uliyyan didn’t stumble but rather fell flat onto the floor. He cried out but the thunder drowned his cries before they reached the family room where Rosette and Line were talking about the weather. Rosette noticed earlier the color draining from Adil’s face. When she went into his room to check on him, she found Adil on the ground, pinned against the bed, his mouth agape, unable to speak.

She tried to lift him into bed. But it was difficult for her to raise his body, and his unconscious state made him even heavier. She rang the bell for the third floor and two servants came down. They yelled when they saw Adil unconscious, which alerted Line, who then hurried into her father’s room. When she saw him on the ground, she froze for a moment. Then she shook herself out of it and took a step to her mother’s side. Her mother helped the two servants manage to finally get Adil into his bed. Everyone waited for the ambulance to come after Rosette phoned the Red Cross. Line’s brooding silence made her anxious.

The house was completely still, including the servants who went quiet too after noticing how calm the two women were. The ambulance arrived and Adil was moved onto the stretcher. Rosette went with him and Line followed in her own car.

* * *

Samir Uliyyan informed me that Adil had been moved to the hospital in Ras Beirut; he was also quick to inform me that Rosette had asked about me and that she wanted to see me. I had been intending to visit Adil in the hospital anyway, and so I visited the very next day.

As soon as Rosette and Line saw me they erupted into sobs. I must be the one remaining person who reminded them of Adil. I am the lone, distant comrade who could still be called a friend of his.

Adil never regained consciousness. He died on the seventh day, the day on which God rested. Rosette and Line left the southern suburbs.

* * *

A whole summer passed during which I heard nothing of Adil’s family. In October I received a package. When I opened it, I found a jumble of papers full of Adil’s creative ramblings, all pretentious analysis and philosophizing . . . his thoughts on writing. But a single paper with large handwritten words stopped me in my tracks: I am not evil. Everything I did, or claimed I did, was simply intended to be terrifying.

Originally written in Arabic.

Scent of a Woman, Scent of a City

by ALAWIYA SOBH

Khandaq al-Ghamiq

It was half past seven in the morning. I didn’t get out of bed, I didn’t hear the usual church bells across from my house in Hamra. Instead I woke up to the chimes of my mother’s voice saying, “The day’s almost over and you’re still sleeping. If I were the ministry, I wouldn’t pay you one cent. It’s seven thirty and you’re still lying around in bed.” My mother’s rosary of words continued until I got up.

My mother can tell the time without a clock. She lifts her finger to the sun to tell the time; I don’t know how she does this. And I don’t know how to use an alarm clock either. I’ve bought clocks many times, but they are soon destroyed or lost without me knowing why. My friend says that my relationship with time isn’t normal. I smiled when she said that and then asked her what time it was. She responded, but just as quickly I forgot what she’d said and so I asked her again. She smiled and patiently answered once more, but perhaps I didn’t hear. One of my bad habits is that I always ask questions but don’t bother listening to the answer. My mother asks and answers herself when she can’t find someone else to talk to. She told me that she’d listened to all the news reports while I was sleeping, and that a woman had been found dead in Khandaq al-Ghamiq.

I didn’t pay attention to what she said and tried to not care. Words like these weren’t strange to my ears.

I opened my eyes wide and I felt an intense swelling in them and all over my body. The exhaustion I felt was like the one you feel at the end of the day. My God, how will I feel by evening? Morning blends into evening, day into night.

I opened the window to cold shadows. The rain was heavy and the howling of storms reminded me that the earth was still turning.

Nature is there in the seasons, but winter grayness has a scent that rises from the street and enters the house, a scent like the one I smelled yesterday evening that’s remained suspended in my nose and on my body since. Before I entered the house and locked the door on another day and another world, I’d tried to walk down the street a bit to take in some air—but the air was not air.

The scent of the Beirut evening was strange, the scent of passersby clung to me. It was not the scent of people’s exhaustion and their old sweat; instead the scent resembled that of dead bodies, the scent of death which emanates from their faces and eyes. In the evening, I wanted to explain this to my friend, but I was afraid that he’d call me crazy or tell me go to a nose doctor—“Perhaps your sense of smell needs curing”—so I didn’t say anything to him. When I awoke to that very same scent in the morning, my fear grew—perhaps the smell of Beirut had changed, but I didn’t want to believe it. Or perhaps the scent was emanating from me.

I observed myself in the bathroom mirror, the scent rising from my face and sticking to the glass like vapor. I thought at first that my breath had stuck to the mirror. I wiped it with my sleeve but the vapor returned to fog it up. I couldn’t see the full reflection of my face; my features were obscured by the vapors of death on the mirror, resembling the death in the city, and resembling the scent of yesterday’s passersby. I tried to convince myself that the problem resided in my nose.

Then I tried to ignore the whole thing, as I had gotten used to facing my problems with instant forgetfulness, but that didn’t help either. I kept telling myself that perhaps I was imagining everything. But I kept hearing my mother’s voice repeat: The crime didn’t happen in that place.

* * *

Through practice, I started forgetting the whole war, not even believing it. Whenever I want to forget something, I sleep. Similarly, whenever it wants to forget, Beirut sleeps.

Sometimes it seems to me that the war didn’t happen. One day city people grew bored of peace, and since they liked to forget, they went to sleep. The city started sleeping on the night of April 13, 1975, and all the people dreamed of war.

It was perhaps the first time in history that thousands of people shared a single dream.

It was really quite strange. I used to always say that to my friend.

“Oh girl, when will you grow up?” he would say, smiling. “What came before the war was a dream, my dear.”

But I didn’t believe him, because I’m more than a thousand years old, if we’re following the Islamic calendar. He smiled again when I said that to him. Then he said, “Why isn’t the dream that old?”

Of course, I didn’t sleep through all those centuries. But my grandmother told me I was born dead, that I was murdered at birth all those years before by my grandfather’s grandfather.

Why he killed me at birth I don’t remember.

My grandmother says that the past is our roots and that the murder of women and girls in infancy is an open secret throughout our land.

But another friend informed me about a woman whose father killed her in childhood because she was too beautiful. She was four years old and looked as if she appeared from a fairy tale. He feared that someone would rape her and so he decided to kill her first.

I grew anxious when she told me this story. She continued, “Perhaps he was afraid of his desire for her—do you think that desire can lead to murder?”

I didn’t answer. I thought, I’m not beautiful. So then why did my ancestor kill me in infancy years before? I don’t remember. But I remember that I was afraid he would kill my sister’s daughter when she was born in the hospital. We didn’t know if my sister would have a boy or a girl, and I waited impatiently and anxiously thr

oughout her labor.

The nurse came out and walked right by me without saying anything so I grew even more worried. I walked up to her and asked, “Is it a boy or a girl?” But she didn’t answer. So I asked another nurse nearby. She looked at me and didn’t answer either. I thought that something had happened to my sister.

I lost it. I stormed into the operating room and asked the doctor. He said, “It’s a girl.” I informed my mother. She said that the nurse was right, the person who informs someone about the birth of a girl shames herself before God for forty days. The nurse who hadn’t replied to me still had a look of shame on her face.

My sister was as beautiful as the white rose on her bed. But I remain full of shame. My mother told me that the news report said that the woman was found dead with her limbs cut off. The security forces’ said that the corpse was unidentified. The incident was believed to have taken place elsewhere. I told her, “Strange. Are you sure?”

She said that the news reported it. With a curious expression, she added, “If the girl hadn’t done anything, no one would have killed her.” Then she continued, “What’s wrong? You don’t look right. You look ashamed.”

I didn’t answer. I turned my face from her and peered out the window, once again feeling ashamed.

* * *

The scent kept filling my nose; I thought that it was coming from my mother.

My mother’s scent was like that of Beirut today, neither that of the village nor of the city. I remember that my grandmother’s scent was different—perhaps it was the scent of the village. I used to be able to distinguish the scent of her house from that of all other houses. I remember when I was young, the beautiful scent would fill my nose upon merely entering her house. I used to search through her little room to try to figure out the secret of her scent, but I never could. I thought about this a lot. I asked her about the secret to her house’s scent, and she would smile and lift the scarf up off her face and her red cheeks, a trace of beauty and a halo of light and goodness bringing fragrance from between her eyes.

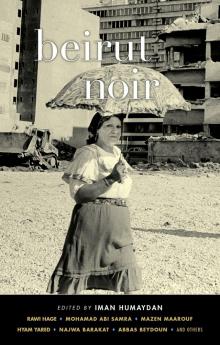

Beirut Noir

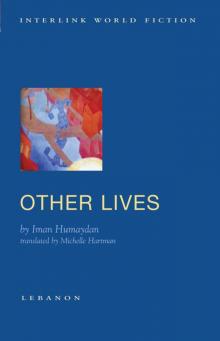

Beirut Noir Other Lives

Other Lives