- Home

- Iman Humaydan

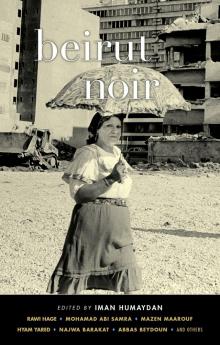

Beirut Noir Page 7

Beirut Noir Read online

Page 7

My wife moved around the house with a nervousness not appropriate to the mood of half past four in the afternoon. The fly too was dismayed to discover that the field of chrysanthemums tasted like cloth and cold glass. My wife then appeared in my range of vision. She calmed down after taking off her shoes with the noisy heels. She came over and kissed the eye. I could only see the space between her breasts and the embroidery on her red bra. They’re color-coordinated. The bra and the shoes.

My wife picked up the eye and dragged it to the bathroom. She put it in the bathtub and started rubbing it with soap and water. She rinsed it with warm water and then did the same again. She said that its smell has become a stench. The eye could only smell expensive perfume mixed with the sweat between her breasts. My wife took off her dress and kept on her camisole. The heat—flames of hot water and the fire of her movements—was making her feel suffocated. Her red bra rose up and made her quavering breasts dangle before they calmed down and stared at the eye.

My wife helped me, using a loofa saturated with soapy foam to reach its back. Her erect nipple approached the eye as though challenging it. Her breast touched the eye gently, perhaps it was tickling the nipple, and perhaps the eye woke and responded. But no. The eye can’t touch the breast—it is fully aware and cognizant of the fact that it isn’t a hand, mouth, or tongue. My wife was angry at the eye and pushed it under the water, leaving it there for a few seconds. The eye thought that its moment of salvation had finally arrived and rejoiced. My wife pushed the eye with her foot after she herself entered the bathwater naked and stretched it out onto its back. The eye relished the feel of her soft skin, but didn’t blink. Her warm belly moved, rising and falling, coming and going, with soap bubbles tickling, breathless and quivering.

The phone rang and my wife picked it up, saying fuzzy words into it, including shoes and four o’clock and useless appointments and something about the importance or the disease of forgetfulness. Meanwhile, the eye submissively waited naked on the towel atop the cold tiles. My wife stopped talking, hung up the phone, and noticed that I’d turned blue, so she held me up to rub me, dry me off, and put on my underclothes while humming a tune, expressing her tender mood of joy. She took me up to the bedroom, swaddled me in my clothes, and asked me if I’d enjoy stretching out on the bed. The eye answered, “No,” so she returned me to my throne on the red sofa.

Our neighbor was standing on the balcony. His face was twitchy as he gazed at our balcony and from there to the street. My wife went out onto the balcony but didn’t raise her glance at him. There was something different in her gait and posture. She picked up the hose and watered the potted plants. She watered them the day before too, the eye thought. Their roots will be worn out if she keeps on like this. Had she perhaps forgotten? Or was something disturbing her and preoccupying her mind? What a question. How could she not be preoccupied when she was feeling the loss of her husband who she loved, cared for, and was devoted to?

* * *

Certain words, images, and ideas are mixed up for me, as if I’ve come across them at the very moment they are changing or taking shape. I can discern only one specific detail without an essence from a voice, color, or form. It’s as if a giant hand cast a veneer of whiteness over the world with barely recognizable things looming behind its tiny holes.

Therefore I feel I should name and enumerate. Anything. Everything. What falls within my range of vision and what I guess or imagine in its surroundings. And I can make a list: leaves, clouds, footsteps, cubed tiles, birds—individually and in flocks—jets of rain, electricity wires, yellow chrysanthemums, the people living in the little screen, curtain rings, electric switches, passersby, lines, spots, dots, cars, electricity poles, voices, potted plants, colors . . . everything. Anything.

I list them so I don’t forget, so I don’t grow too distant from a world whose mayhem still reaches me and whose chaos still confuses me. I still have to reside here, even if only for a while. I rely on my exercises to pass time, chewing on a language as if I’d never learned it, as if it had suckled me, turned on me like a serpent, to bite off words whose taste had died long ago and whose return continues to hover within my range, like the whispering of water. Capturing the wind. A memory that wobbles on the edge of the tongue. A city hidden by sand where a fragment of a vase finally revealed a thread linking it to the urban fabric. I am the specter of a language swaddled by the wind.

I hear: “Alif, ba, ta, tha’” (“A, B, C, D”) . . . I see letters themselves repeating. I see them passing against a black background, like train carriages, hand in hand, and I wait patiently for one letter after another to cross my optical screen. But only emptiness, silence, and silly letters start forming themselves again in combinations not organized by meaning or name. Thus passed “the years of my absence,” as my wife liked to call the period when I was away from her. The expression makes me laugh and I pity her when I remember her saying it, her tongue faltering breathlessly, scared someone might clarify it or a rude guest might correct her.

During “the years of my absence,” I used to sit in the darkness of my soul and count. Counting relaxed me and it still does. It circulates through me like drugs. Numbers penetrate deeply, then begin to bubble up from inside like soap. They bubble up, ossify, and increase until they fill me, scraping the sticky viscous muck and everything that hurts, disturbs, and sickens. Places with no light, sound, or breeze whatsoever help me concentrate. I don’t complain about staying in places that can barely accommodate my feet if I stretch them out. I can stay squashed up on top of myself, eye closed, absorbed in numbers until passing out, not sleeping, after which I start trying to keep track of how long I was out.

When they took me out of the “hole,” as they called it, I kept cheating, starting fights, and quibbling until I gave them an excuse to put me back there, my bloody body swollen with bruises and cuts. Neither severe beatings nor humiliation, nor other types of physical pain made me cry. Only my memory, my anguish, and my regret for what I thought was love and kindness, but at the end of the day was worse than evil.

* * *

My brother—he had no name except “my brother,” since he only answered when I called him that—didn’t like names. One sound sufficed for him, as in when he chose only one letter from my name—Kaf—and started calling me that, stretching it out, as he did when he started calling my parents “Maaaaaa” and “Paaaaaaaa.” They forced him to count and, unlike me, counting tasted like a kind of torture to him. Addition and subtraction required him to use his fingers and other things. That was until I found him the solution in an imaginary bag, which we sketched out together in his mind, into which he put every number that he had previously kept in his hand, waiting to complete the computation process.

He’d scream “Kaaaa!” then bang his head against the ground if he didn’t find me next to him. When I’d come, he’d gurgle like a fountain, hugging the tree as he would a human—living beings and inanimate objects weren’t different to him. My mother’s female relatives said, “God bless the Creator of two brothers who don’t resemble each other at all—either in looks or temperament. Praise be to Him, the one who beats you with one hand and supports you with the other” . . . I started thinking about the one they called “Praise be to Him.” The one who supported my mother when she was giving birth to me and beat her when she gave birth to my brother, as he fell from her belly onto the ground and hit his head on the tiles, rolling onto his face, his eyes shrunken, his limbs diminished. Fearing this “Praise be to Him” would direct another blow at him, perhaps as revenge, my brother didn’t want to grow up as other children do.

Despite this, for some reason I don’t understand—and contrary to the comments of everyone who spun around in our orbit, including our parents—I started to feel we were twins: as if he were the night and I the day, he the white and I the black, he the letter and I the dot. I remained amazed and astonished, not understanding how people didn’t see the resemblance between us, to the point where I pu

t all the blame for this on “Praise be to Him,” who confused people. He put a soul in me which had my brother’s body shape, and he instilled in my brother a soul that matched my own looks. So my soul lived as a stranger, having nowhere to settle down, in exile in a place it didn’t know, where it didn’t fit in, harboring a desire to leave and go where its twin was hidden, locked up in shackles and dirt.

They pitied him and I envied him. Lying in bed, I wished he were the one about whom people said, “Beautiful features and a good head on his shoulders,” and I were the one about whom they said, “Poor thing, deranged looks and a deficient mind.” Because of my jealousy I started acting like he did while holding his hand, walking together to school: I would take my hand from his, making sure no one was watching, and then I’d start to cover everything with wet kisses. I’d open up my schoolbag and eat my snack before the bell rang, marking the arrival of the ten o’clock break, or I’d throw it to a homeless dog or stray cat, or I’d put it in a hole in a tree stump, and on top of all that I’d kiss it because . . . because it was there, on the side of the road. I’d take off my school uniform and throw out the coins in my pockets. If my shoes were too tight or a pebble got into them, I would take them off too and walk barefoot, not feeling pain, cold, or shame. My brother’s laughter would accompany me, rising up behind me and causing a huge bevy of leaves to fall from the trees onto us.

My brother was the only one who missed me after what befell me. In any case, he is the only one I missed too. Others would pass by the eye and not linger or tarry. Passersby, people in transit, visitors. Capturing the wind. I don’t remember any of their features, and they don’t leave any trace on me. The faces which come back to me are themselves few, wild, and don’t tolerate any intimacy. Sometimes I can put names to them, when the waters of memories explode within me; I’m not aware of them flowing down in my lower regions.

This is how “Ta” came in disguise, hiding behind memories that weren’t his, despite all my miserable attempts to make him go away. Ta, who I fell in love with when we were still children. Because he stopped to watch me play with my brother. He didn’t laugh. He didn’t ridicule. Because he approached us trying to be friendly, begging us to include him in our clique. Because I didn’t understand at the beginning and didn’t believe. Because I prevented my brother from hugging him and kissing him like he did with every other stranger. Because I started noticing him every day following us from a distance. Like a dog. And because I saw him one day playing with my brother, when he didn’t see me; he picked my brother up off the ground, wiped his runny nose, straightened his clothes, and kissed his head. And because when I approached, he stopped silently and asked, “What’s his name?” I said, “My brother, he doesn’t have another name.” He said, “Then he’s my brother too!”

* * *

AAAAAAAAH . . .

My wife rushes over to me, alarmed. My eyes are bulging, fluids streaming out of them, which she catches with her hands so they won’t soil her red sofa. She asks me what’s wrong, repeating, “Do you want me to call the doctor?”

What doctor? And what use are all the doctors in the world to me if I can’t turn back the wheel of time even a few seconds? A few seconds, not more, to push my life to the junction, which would deviate from a hell whose fires only subside to crane up its neck anew. A few seconds, my God, and I would rewind parts of the tape. I would see Ta walking with my brother and playing with him, not noticing me after he lifted him from the ground, straightened his clothes, and wiped his nose. I would go over to them and remain silent, not uttering a sound, until he asked me what his name was. I would answer, “My brother. You aren’t related to him and if you come near him again, I’ll bust your nose and even God won’t be able to fix it” . . . So Ta, who was cowardly by nature, would have walked away frightened, head bowed, leaving my brother and me alone, never to return.

But I didn’t rebuke him, I didn’t make him walk away, and Ta got closer and closer to us until he started haunting us. On the way to school, in school, and on the way home. We were almost like relatives—even the family on both sides followed us. In any case, they didn’t have a choice. As we grew older his infatuation with and devotion to us increased, as did our trust and devotion to him. I even started relying on him and leaving him alone with my brother, whenever desire called me. I was at the age of discovering desire in all its forms and I would forget my brother or to wonder about Ta’s devotion to him. I would forget to think about how strange it was that he wasn’t passionate about life like I was. So I’d push any doubts about him or rebukes to my own conscience right to the back of my mind.

* * *

When I discovered what was happening, they were together in the garage where my parents had set up a place for us to play when we were little. As we got older, they transformed it into a kind of space to hang out where we could have our forbidden dreams, secret conversations, and crazy music in private. My brother would rejoice when we’d take him there and he loved spending time there with us, since he could feel that perhaps he was like us, equal to us, far from the eyes of the family. We would enter, and he would explode like a volcano because it didn’t matter if we threw our things around in a mess or if havoc was wreaked on the place. We’d stand idly watching him playing our drums, strumming the strings of instruments very dear to our hearts, or ripping up pages of magazines we’d bought. The garage remained our oasis for many years. When I grew up and fell in love with my aristocratic rabbit and she was determined that we get married or break up, Ta convinced me to accept a compromise. He would stay with “our brother” and take over his care and protection so my parents—hardworking government employees who only came back home late in the evening—wouldn’t send him where disabled people like him were sent . . .

* * *

I heard a moan and rattle of the throat, so I looked through the keyhole and saw Ta there, standing with his trousers scrunched up around his knees, his naked bum convulsing. I thought, He’s having an intimate moment, I won’t disturb him, so I took a couple of steps back. But just then I heard my brother’s voice, weak and strangled as though a large hand were covering his mouth. Could Ta be having sex with a girl when my brother is there watching him? I wondered if he’d offered to stay with my brother and watch over him just so it would be possible to make love in secret? Who is this girl he’s hiding from me? Why the need for all these secrets?

The voice got louder, so I bent down again and this time I saw Ta standing to the side, stroking his erect member, putting strawberry cream on it—the kind my brother was so fond of—and showing it off, adorned with sweets, to a person who the keyhole wouldn’t allow me to discern until Ta moved backward and my brother’s distorted, wretched face appeared before me, soiled with a mix of cream and semen.

I don’t know how I got the door open and reached him, faster than an untamed wind, stronger than an earthquake, and started hitting, punching, kicking, and beating him. Until what was underneath me was just a mess of features covered in blood and urine. I didn’t regain consciousness from my waking coma until my brother took my hand and pulled me—us—out of the garage. I didn’t want to go with him, as though I intuited from that moment that I’d lost the right to be outside, anywhere outside. He sat me on the doorstep of our house and, perching down next to me, put his head on my shoulder like he used to when he was sleepy. He cried a little and then fell asleep. When he woke up, it was already evening and my family came, with Ta’s family behind them, bringing the police, who took us away—me to jail, Ta to the cemetery, and my brother to one of those centers they call “special.”

During “my absence,” I learned that my brother had lost his appetite and that he used to ask for me from morning to night, while banging his head on the wall, repeating, “Kaaaaaa.” Even looking at him makes your heart bleed, that’s what my wife told me on one of her visits, after I entrusted her with his care. Whenever he saw her he would get more agitated and angry until the nurses would remove him, restraining

his arms and legs and gagging him. Finally, she asked my permission to stop visiting him since every time he expected to see me and not her. My family stopped their visits to him too. But every time I asked about him, they’d all reassure me that he wanted for nothing, that he was in good hands, and that specialists were caring for him. I thought that prison came as a mercy to my parents, since it delivered them of me, because had I remained outside I wouldn’t have let them do this to him and I would have inevitably committed two more crimes without batting an eyelid.

The eye knows that my brother died because of his loss—that he withered and decayed, oppressed and wanting, missing both me and Ta.

What I can’t stand to think about is the certainty that he was—despite all that happened to him for so many years—still attached to Ta and loved him, unable to feel hatred or malice. When I think about that, it ignites remorse and defeat in me. I feel a burning fire inside myself, spreading through every inch of my insides, not leaving a trace on what originally were destruction and ruins.

Years have passed since this incident and the end of my sentence, which elapsed after five years since they determined mine was a “crime of passion,” as the lawyer told me. As though it was somehow dictated by my passion. My passion for whom? My passion for my brother? My passion for Ta? Or my passion for our small family, made up of the three of us, motivated by the fact that our families were busy and not looking after us. This led to a desire within us to find that missing care by providing it to others. So I didn’t search for an explanation for what happened, though it was the image of myself, scattered around like a doll whose limbs had been torn off, organs removed, and features smashed—that’s what worried me. That’s how my bodily functions and senses were all disrupted—my heart died, my intestines were squashed, my liver ripped out, and all that was left was an eye.

Beirut Noir

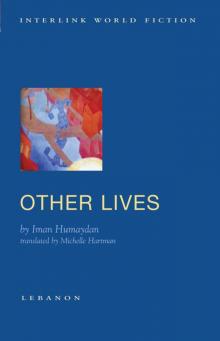

Beirut Noir Other Lives

Other Lives